I’ve written before about Hamilton’s pivotal role in the the Election of 1800. Below are some excerpts from Hamilton’s letters in December 1800 on the presidential contest between Jefferson and Burr.

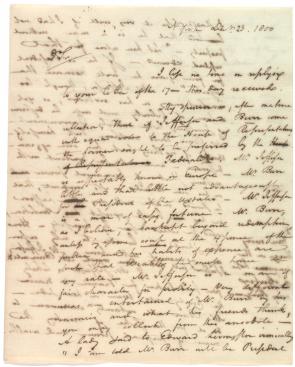

On December 23, 1800, Hamilton wrote to Harrison Gray Otis, a prominent Boston Federalist expressing his fears about Burr’s character and boundless ambition:

Burr loves nothing but himself; thinks of nothing but his own aggrandizement, and will be content with nothing, short of permanent power in his own hands. No compact that he should make with any passion in his breast, except ambition, could be relied upon by himself. How then should we be able to rely upon any agreement with him. Jefferson, I suspect, will not dare much. Burr will dare every thing, in the sanguine hope of effecting every thing.

A digitized image of Hamilton’s original letter to Gray is available via the Gilder Lehrman Collection.

In December 1800, Hamilton wrote to Oliver Wolcott, Jr., President Adams’ Secretary of Treasury (who would resign from the position days later) with the purpose of dissuading him from favoring Burr’s candidacy. Wolcott, Jr. and other Federalists were so opposed to Jefferson’s policies that many saw Burr as a more palatable alternative. Hamilton fiercely resisted this position:

There is no circumstance which has occurred in the course of our political affairs that has given me so much pain as the idea that Mr. Burr might be elevated to the Presidency by the means of the Fderalists. I am of opinion that this party has hitherto solid claims of merit with the public and so long as it does nothing to forfeit its title to confidence I shall continue to hope that our misfortunes are temporary and that the party will ere long emerge from its depression. But if it shall act a foolish or unworthy part in any capital instance, I shall then despair.

Such without doubt will be the part it will act, if it shall seriously attempt to support Mr. Burr in opposition to Mr. Jefferson. If it fails, as after all is not improbable, it will have rivetted the animosity of that person, will have destroyed or weakened the motives to moderation which he must at present feel and it will expose them to the disgrace of a defeat in an attempt to elevate to the first place in the Government one of the worst men in the community. If it succeeds, it will have done nothing more nor less than place in that station a man who will possess the boldness and daring necessary to give success to the Jacobin system instead of one who for want of that quality will be less fitted to promote it.

Let it not be imagined that Mr. Burr can be won to the Federal Views. It is a vain hope. Stronger ties, and stronger inducements than they can offer, will impel him in a different direction. His ambition will not be content with those objects which virtuous men of either party will allot to it, and his situation and his habits will oblige him to have recourse to corrupt expedients, from which he will be restrained by no moral scruples. To accomplish his ends he must lean upon unprincipled men and will continue to adhere to the myrmidons who have hitherto seconded him. To these he will no doubt add able rogues of the Federal party; but he will employ the rogues of all parties to overrule the good men of all parties and to prosecute projects which wise men of every description will disapprove.

These things are to be inferred with moral certainty from the character of the man. Every step in his career proves that he has formed himself upon the model of Catiline, and he is too coldblo[o]ded and too determined a conspirator ever to change his plan.

On December 16, 1800, Hamilton wrote to Wolcott again:

“There is no doubt but that upon every virtuous and prudent calculation Jefferson is to be preferred. He is by far not so dangerous a man and he has pretensions to character.

As to Burr there is nothing in his favour. His private character is not defended by his most partial friends. He is bankrupt beyond redemption except by the plunder of his country. His public principles have no other spring or aim than his own aggrandisement per fas et nefas. If he can, he will certainly disturb our institutions to secure to himself permanent power and with it wealth. He is truly the Cataline of America—& if I may credit Major Wilcocks,he has held very vindictive language respecting his opponents.”

In both letters to Wolcott, Hamilton describes Burr as the Catiline of America, referring to a Roman Senator of the 1st Century BC who attempted to overthrow the Senate and the Roman Republic, but was stopped by Cicero and then exiled.

On December 24, 1800, Hamilton wrote to Gouverneur Morris:

Another subject—Jefferson or Burr?—the former without all doubt. The latter in my judgment has no principle public or private—could be bound by no agreement—will listen to no monitor but his ambition; & for this purpose will use the worst part of the community as a ladder to climb to perman[en]t power & an instrument to crush the better part. He is bankrupt beyond redemption except by the resources that grow out of war and disorder or by a sale to a foreign power or by great peculation. War with Great Brita[i]n would be the immediate instrument. He is sanguine enough to hope every thing—daring enough to attempt every thing—wicked enough to scruple nothing. From the elevation of such a man heaven preserve the Country!

He followed this up with a second letter to Morris two days later on December 26, 1800, stating:

“That on the same ground Jefferson ought to be preferred to Burr.

I trust the Federalists will not finally be so mad as to vote for the latter. I speak with an intimate & accurate knowlege of character. His elevation can only promote the purposes of the desperate and proflicate. ⟨If t⟩here be ⟨a man⟩ in the world I ought to hate it is Jefferson. With Burr I have always been personally well. But the public good must be paramount to every private consideration. My opinion may be freely used with such reserves as you shall think discreet.”

[…] Jefferson or Burr? Hamilton’s Letters in the Election of 1800 […]